I first came to this topic because Lynn and I were trying to decide what to do. We’d always thought we’d be cremated, but green burials seemed like a good idea and if I’m honest, it was the lovely basket coffin with its cotton bedding we saw on a hospice tour of Stubberfields Funeral Home that really attracted me. So tasteful. So comfortable.

And the Cranberry cemetery is beautiful. A little sedate – not much room for flair – but peaceful and sunny. If we were cremated, we could also go to the Kelly Creek cemetery. It is lovely and crazy. But do our kids want to do something zany to remember us by? It’s not really their style. We’ll have to take them there and see what they think.

While researching this, my mother, who was 99 and in good health, suddenly declined and we were, while mourning her death, busy putting into action her wishes about cremation, burial, and funeral. It brought back lots of memories, or their lack.

When my dad died in 1970, it was very sudden – post-polio syndrome. He was right upstairs when my mom came down to tell us, but I didn’t go to see him. I don’t know why. My brother remembers going. I was in a very strange place. Friends came by and what I mostly remember is I wasn’t wearing my usual mascara and eyeliner. Of course, no one noticed, but I stopped wearing it after that. It seemed pointless. Went back to school within a day or two.

Dad wasn’t cremated until his parents were able to get here from Saskatchewan. They wanted to see him. I think they asked me if I wanted to go with them to the funeral home, but I didn’t. Was he in the church for the funeral? I don’t remember. As I said, I was in a strange sixteen-year-old frame of mind.

I must have had some notion that cremation meant the body disappeared – that there was nothing left. There was no talk of ashes, of burying them or of spreading them. I didn’t think much about it until years later. I asked Mom. She’d left them at the funeral home. He was gone, she said. The ashes held no significance for her. After that Stubberfields tour, I asked the director Patrick Gisle what he did with ashes left behind. I actually wondered if they could still be there, fifty years later. He told me it happens regularly and he has a few quiet places he spreads them.

I suspect Dad’s parents would have liked to bury them in the lovely little prairie cemetery where they’re now buried. There’s something beautiful about the expanse of land and that big prairie sky. Dad might have liked it too. He was at heart, I think, a prairie man. My friend Margaret’s family has a private graveyard in Manitoba, near what’s left of the family farm. On her regular trips to the small town where her brother David lived until his death a couple of years ago, she tends to the graves, which go back at least four generations. She has a deep sense of attachment to the place and its history. She’s thinking she’ll have her ashes buried there.

Cemeteries give a kind of permanence to the disposition. They form part of the historical record and can become places of both private and more public pilgrimages. I remember visiting, in 1977, the grave of the poet John Keats in the Protestant cemetery in Rome just after going to the rooms beside the Spanish Steps where he died of TB in 1821. He was 25, a year older than I was then. I’d been reading his letters. His friend, painter Joseph Severn, described his death: In the afternoon he uttered his last words ‘Severn-I–lift me up–I am dying–I shall die easy–don’t be frightened–be firm, and thank God it has come!’ That night he expired, ‘so quiet’ that Severn still thought he slept. I found myself in tears – so moved by his youth and his generous heart. His epitaph broke my heart: Here lies one whose name is writ in water.

Although tombs can become the focal points of terrible conflict, visiting the graves of celebrated figures connects us to our cultural and religious communities, whether it’s Jim Morrison in Paris or the Taj Mahal in Agra. On a local level, participating in the cremation, the interment of the body or the spreading of ashes connects us on a more intimate level to our family and friends.

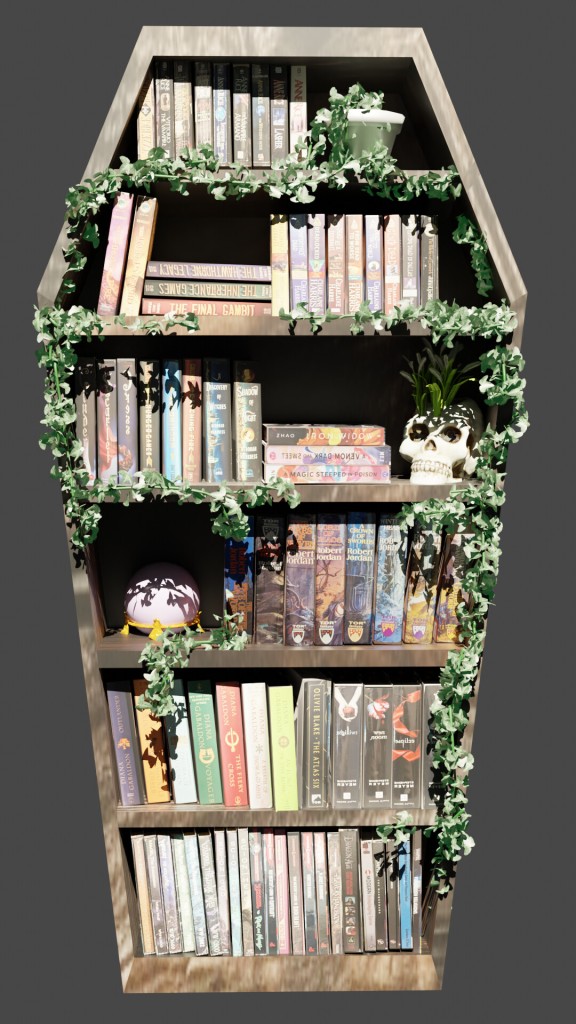

The past fifty years, at least in North America and Europe, have seen the creation of rituals to replace the Christian traditions many of us have left behind. Children decorate their grandparents’ coffins, ashes are turned into jewelry or sculpture, spread from helicopters (or in the case of Hunter S. Thompson, shot out of a cannon). Notes are tucked into urns, shrouds are woven by the intended user and proudly displayed, coffins are built in distinctive shapes; a popular example can be used as a bookcase until it’s needed for burial.

To reduce both financial and environmental expenses, Community Supported Dying qathet lends out a handmade and decorated coffin to transport an enshrouded body to its burial site at the Cranberry Cemetery.

Borrowing a Tibetan tradition, we started hanging prayer flags after a trip to Nepal, liking the idea of the wind carrying prayers out into the world, helping us all in the work of practicing compassion, of relieving suffering. The spot we chose on our property near Smithers funneled the wind blowing through from one mountain range down the canyon of the creek we lived beside into the watershed of the Wedzin Kwa and on to the great Skeena passage. I sewed together my mother-in-law’s beautiful hankies in her memory; we made flags out of old linen napkins with poems and blessings written on them. We spread ashes among the willows and aspens facing into the sunniest opening in the canyon walls. We created our own sacred place.

But then we moved. It’s on someone else’s property now.

We hung prayer flags from the lighthouse beside our house at Grief Point, or χakʷum by its ʔayʔaǰuθəm name, but it doesn’t have the same sense of private pilgrimage. The land was alienated in the 1890s and our subdivision was built in the 1960s. Tla’amin artifacts were found during the extensive excavation work, underscoring the ways in which precious places can be overrun, lost.

Cemeteries are perhaps an attempt to keep that sense at bay. My grandma, aunt and soon my mom’s ashes will be buried in Cranberry. My sister has reserved a plot there too. I suspect in one form or another Lynn and I will end up there. Still not sure what form that might take.

- This piece came out of research done for an article by the same name published in qathet Living for its Memento Mori issue in November 2023 and a gathering I led for one of the qathet Art Centre‘s Memento Mori events November 15, 2023.

Such an interesting a thought provoking post Sheila. It is a fascinating subject and one that warrents much discussion. Thanks for starting a conversation.

Sheila…found this a fascinating blog with more to think about after life as we know it. Thank you. For your insight, your candidness, and your reminiscences.

We have had the most interesting conversations around this topic over the past few months … still don’t know what we’re going to do.